To mark Graham Greene’s birthday we are publishing the talk that Michael Hill would have given at the Graham Greene International Festival which would have been taking place now.

‘Murder didn’t mean much to Raven’

A Gun for Sale in context

I read my first Graham Greene novel, I think, sometime in the 1970s. I liked what I read, and read some more, so by the 1990s I had read them all, including his two suppressed novels. I had hoovered up all his other published writings, too. So when the centenary of Greene’s birth came round in 2004, there was nothing new to read. My solution was to re-read all the novels, but this time in the order in which he had published them, starting with The Man Within and ending with The Captain and the Enemy. It’s an approach I can thoroughly recommend – reading the novels in order gives a strong sense of the progress of his career as a writer, the gradual development of his distinctive voice and style, his concerns and outlook, and yields the occasional dead end. And since doing that in 2004, I now realise that when I come to re-read any Greene novel I am always half-consciously doing this contextualising, putting the work in question in the more general context of his development as a writer.

But I’m aware of another context too. My own academic training was not in literature but in history, and at least one of the attractions of Greene’s writing for me is the historical context of his novels – with only a couple of exceptions he was a chronicler of the twentieth century, and there is generally in his novels a very strong historical background of which I am aware or keen to know about.

But I’m aware of another context too. My own academic training was not in literature but in history, and at least one of the attractions of Greene’s writing for me is the historical context of his novels – with only a couple of exceptions he was a chronicler of the twentieth century, and there is generally in his novels a very strong historical background of which I am aware or keen to know about.

So now I am explicit about it, I’m always these days reading a Graham Greene novel with these two frameworks in my head – how it fits into Greene’s progress as a writer, and how it fits the history of the time in which it is set. And I’d like to look at these two contexts in relation to an unjustly neglected Greene novel, scarcely ever mentioned at these Festivals – A Gun for Sale, from 1936.

Part 1: ‘I like thrillers.’ (Anne Crowder, A Gun for Sale)

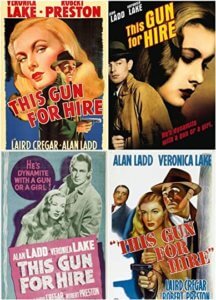

Let’s start with the literary context, and say a little about where the novel sits in Greene’s development as a writer. It was published in July 1936, his seventh novel. He had started writing it after his return from his trek across Liberia in 1935 and finished it, we know, on 4 January 1936, during a very busy period, which also included the seeing through to publication of his previous novel England Made Me, the writing of his travel book Journey Without Maps and of various short stories, extensive book reviewing and now, film reviewing for the Spectator. A Gun for Sale was written with all the confidence and speed of youth – he was now in his early 30s – and a growing experience as an established writer who was finding his voice. He had a wife and daughter to support, and soon, a son too, and he was making the most of his writing talent. In 1935 Greene and his family had moved from Oxford to 14 North Side, Clapham Common, now perhaps for the first time confident of being able to earn a full-time living with his pen. And A Gun for Sale helped in that – sales of the hardback were not remarkable (5,000 copies in the UK, 2,100 in the US), but startlingly the film rights to the novel were sold to Paramount even before publication for the tidy sum of £2,500. (It was eventually made into a film in 1942.)

There’s one other thing to point out about the publication of A Gun for Sale. It was the first Greene book to be given the formal title ‘Entertainment’, signalling the intention of something popular and commercial; Stamboul Train was similarly now listed as an Entertainment, while The Man Within, It’s A Battlefield and England Made Me were Novels. These categorisations suggest that by the mid-1930s Greene was for the first time publicly acknowledging that his career was that of a writer, someone whose works could be listed and put into different categories of literary aspiration. And in calling A Gun for Sale an ‘Entertainment’, Greene’s priorities with the book were clear: he was indulging his penchant for melodrama and aiming at a commercial market, without much pretension of literary merit. Greene referred to A Gun for Sale as a ‘thriller’ or a ‘shocker’; whether it’s more than that remains to be seen.

What Greene had come up with, in plot terms, was a John Buchan-style double chase. James Raven, a hired killer, assassinates a central European politician and thereby sparks off a general European crisis leading, it seems, to war. But he has been paid in stolen currency, so he pursues those who have tricked him, and he finally tracks down the Mr Big – Sir Marcus, head of a steel firm in the English Midlands who had ordered the killing precisely to provoke a war crisis and boost his company’s profits. In turn, Raven is pursued by the police. He comes across a showgirl and a whole range of secondary characters and situations, leading eventually to a denouement in which Raven kills two more people, including Sir Marcus, but is shot himself. The war crisis subsides as quickly as it has arisen.

Such a bald plot summary scarcely does full justice to the book, but it does point to one element of Greene’s progress as a writer – that by 1936 he still hadn’t got a proper sense of a plausible plot. Critics are right to point, for instance, to some pretty big coincidences in the plot. The showgirl Raven kidnaps, Anne Crowder, just happens to be the fiancée of Mather, the policeman pursuing Raven; Davis, Raven’s paymaster, is also the financial backer of the revue Anne is appearing in; Davis, pursued by Raven, happens to catch the same train out of London as Anne; various characters involved in the plot intersect by chance at a church jumble sale; and much later, we learn that Sir Marcus attended the same orphanage as the politician he has had killed. Most comical of all is an extraordinary plot detail: Davis discovers that Anne Crowder is in cahoots with Raven, and, in a manner not described, he shoves her up a chimney; there she is discovered accidentally the following day by Raven himself; and within moments of being released, Anne is as perky as if nothing has happened. By my reckoning it is easily the most bizarrely implausible plot detail in all Graham Greene’s books. Perhaps it is some kind of private joke on Greene’s part; if so, I’m not privy to it.

So like the later ‘entertainments’ The Confidential Agent and The Ministry of Fear, Greene’s thriller is rather too reliant on coincidence and implausibilities, but it nevertheless forms a tightly-structured, gripping tale: A Gun for Sale is under much firmer authorial control than, in particular, The Confidential Agent. The opening section, in which Raven kills the Minister and his secretary, is a brilliant tour de force – short sentences, action clearly and concisely rendered, a classic example of the cinematic qualities of Greene’s writing; perhaps the best opening section in all of Greene’s novels. Much of the novel is set at night and/or in fog, giving it a suitably noir feel. The book also shows Greene’s command of the cliff-hanger, and keeping the reader waiting – at one point we are left wondering what has happened to the endangered heroine Anne for fully forty pages; and later, a student rag day plays out while we are unsure of Raven’s whereabouts in his pursuit of Sir Marcus. Here is Greene in control of the thriller form.

By 1936 Graham Greene had also mastered one of his trademark skills as a writer – the depiction of place. Much of the novel is set in Nottwich, his name for the Nottingham he lived and worked in in the mid-1920s, and here is his wonderful description of early morning Nottwich one December morning, as a train pulls in:

There was no dawn that day in Nottwich. Fog lay over the city like a night sky with no stars. The air in the streets was clear. You had only to imagine that it was night. The first tram crawled out of its shed and took the steel track down towards the market. An old piece of newspaper blew up against the door of the Royal Theatre and flattened out. In the streets on the outskirts of Nottwich nearest the pits an old man plodded by with a pole tapping at the windows. The stationer’s window in the High Street was full of Prayer Books and Bibles: a printed card remained among them, a relic of Armistice Day, like the old drab wreath of Haig poppies by the War Memorial: ‘Look up, and swear by the slain of the war that you’ll never forget.’ Along the line a signal lamp winked green in the dark day and the lit carriages drew slowly in past the cemetery, the glue factory, over the wide tidy cement-lined river. A bell began to ring from the Roman Catholic cathedral. A whistle blew.

That seems to me to be a Graham Greene who has found part of his authorial voice.

There’s another feature of A Gun for Sale which is quite typical of Greene the novelist, and little remarked on. Writing about the 1930s in Ways of Escape, Greene refers to ‘my early passion for playwriting which has never quite died.’ He continues, ‘In those days I thought in terms of a key scene – I would even chart its position on a sheet of paper before I began to write. “Chapter 3. So-and so comes alive.” Often these scenes consisted of isolating two characters … It was as though I wanted to escape from the vast liquidity of the novel and to play out the most important situation on a narrow stage where I could direct every movement of my characters. A scene like that halts the progress of the novel with dramatic emphasis, just as in a film a close-up makes the moving picture momentarily pause.’ Greene suggests that this typical set-up began for him in Stamboul Train, with the scene of Coral Musker and Dr Czinner in a railway shed; and we might note other examples in his later fiction, from Harry and Rollo atop the Prater Wheel in The Third Man, to Fowler and Pyle in the watch tower in The Quiet American, to Jones and Brown alone in the cemetery in The Comedians, and the long scenes of kidnappers and victim in a hut in The Honorary Consul. In A Gun for Sale the equivalent scene takes place between Anne and Raven in a railway shed in the course of a cold night. Their conversation gives us background to Raven’s poor upbringing and his sour outlook on life, and gives the hired gun a new insight into the man he has killed; it even covers belief in God, and the nature of dreams. And crucially, it leads Raven to trust Anne, and to enlist her help in evading the police and hunting down Sir Marcus. It is a remarkable scene, one which occupies about ten per cent of the whole book, and it is part of a long tradition in Greene’s writing.

Raven’s conversation with Anne about God and prayer is part of a religious theme in the novel that’s worth mentioning. Graham Greene was famously irritated when critics suddenly labelled him a ‘Catholic writer’ after discovering religious themes in Brighton Rock, rejecting the label and feeling as if no-one had read any of his earlier work. A Gun for Sale bears out this irritation. It’s perhaps no coincidence that the plot unfolds in the days leading up to Christmas, and allows Greene to put into Raven’s mind and mouth his reactions to the Christian story. In particular, there’s a long passage where Raven stops outside a religious shop in whose window is a plaster display of Madonna and Child in the stable, and books of devotion; he reacts with bitter anger, remembering his own brutal treatment in a children’s home, reflecting: ‘They twisted everything; even the story in there, it was historical, it had happened, but they twisted it to their own purposes. They made him a God because they could feel fine about it all, they didn’t have to consider themselves responsible for the raw deal they’d given him.’ So Raven feels a ‘horrified tenderness’ towards ‘the little bastard’, born like Raven to be double-crossed. If the religious element in A Gun for Sale is not as thoroughgoing as in Brighton Rock, it is there nevertheless, embedded in the thriller format.

Finally on matters literary, some words about Greene’s characterisations in A Gun for Sale. It’s striking how many of the support characters are caricatures or grotesques, or have tantalising back stories, as if Greene has more imagination than he can quite cope with. There is a stammering policeman. There is Dr Vogel, the back-street surgeon. There is Mollison, Sir Marcus’s valet, who hates his master. There is Joseph Calkin, the fat, excitable Chief Constable of Nottwich who yearns once more for the power to run the local military tribunal. There is Davis, a man with a greed for cakes and showgirls. There is Buddy Ferguson, the second-rate medical student who organises the student ‘rag’ in Nottwich. And there is Acky, the deranged defrocked clergyman and his evil wife Tiny, who run a bawdy house – characters so startling that they jump off the page and threaten, like Minty in England Made Me, to highjack the story.

In contrast there is Jimmy Mather, the policeman who hunts down Raven. Greene writes in Ways of Escape that he can imagine Mather ‘to have been trained as a police officer under the Assistant Commissioner of It’s A Battlefield’; in just the same way we might think his girlfriend Anne Crowder to be a friend of the plucky, good-natured chorus girl Coral Musker in Stamboul Train. Mather is a PC Plod who has been promoted – efficient and dull, ordinary and predictable. The closest he comes to a personal motto is ‘it’s the routine that matters’, and we are told that his response to his fiancée Anne is not love, but ‘a dumb tenderness’. As for Anne: that good-natured, resourceful chorus girl knows how to get out of a tight corner, survives by my reckoning three attempts on her life, and having spent a night stuffed up a chimney is within minutes of her rescue able to turn a gun on Acky and effect her escape. I think Judith Adamson’s wait for Aunt Augusta would not have been so long had she considered A Gun for Sale: Anne Crowder is easily the sparkiest Greene female before Travels with My Aunt. And though the book ends with Anne returning home with Mather and sighing, ‘Oh … we’re home’, it’s impossible to believe that their marriage will be contented. Anne would have to leave her plodding hubby, or just die of boredom. Anne’s future is no brighter than Rose’s at the end of Brighton Rock.

In contrast there is Jimmy Mather, the policeman who hunts down Raven. Greene writes in Ways of Escape that he can imagine Mather ‘to have been trained as a police officer under the Assistant Commissioner of It’s A Battlefield’; in just the same way we might think his girlfriend Anne Crowder to be a friend of the plucky, good-natured chorus girl Coral Musker in Stamboul Train. Mather is a PC Plod who has been promoted – efficient and dull, ordinary and predictable. The closest he comes to a personal motto is ‘it’s the routine that matters’, and we are told that his response to his fiancée Anne is not love, but ‘a dumb tenderness’. As for Anne: that good-natured, resourceful chorus girl knows how to get out of a tight corner, survives by my reckoning three attempts on her life, and having spent a night stuffed up a chimney is within minutes of her rescue able to turn a gun on Acky and effect her escape. I think Judith Adamson’s wait for Aunt Augusta would not have been so long had she considered A Gun for Sale: Anne Crowder is easily the sparkiest Greene female before Travels with My Aunt. And though the book ends with Anne returning home with Mather and sighing, ‘Oh … we’re home’, it’s impossible to believe that their marriage will be contented. Anne would have to leave her plodding hubby, or just die of boredom. Anne’s future is no brighter than Rose’s at the end of Brighton Rock.

Then there is the central character James Raven, a lonely, tormented young man, emotionally cold and alienated from society. He has a hare lip and has never been with a woman; his criminal father was hanged, his mother committed suicide; he has had a brutalised childhood; he is as efficient a killer as that other James, Mather, is a policeman; and he has no moral scruples – ‘Murder didn’t mean much to Raven.’ He responds to Anne, the first person who ever trusts him, but ultimately he remains a cold-hearted killer who must meet justice. Most critics have seen Raven as an earlier version of Pinkie in Brighton Rock – as Graham Greene himself did. It’s worth here quoting Greene at length on Raven, from Ways of Escape:

Raven the killer, seems to me now a first sketch for Pinkie in Brighton Rock. He is a Pinkie who has aged but not grown up – doomed to be juvenile for a lifetime. They have something of a fallen angel about them, a morality which once belonged to another place. The outlaw of justice always keeps in his heart the sense of justice outraged – his crimes have an excuse yet he is pursued by the Others. The Others have committed worse crimes and flourish. The world is full of Others who wear the mask of Success, of a Happy Family. Whatever crimes he may be driven to commit the child who doesn’t grow up remains the great champion of justice. ‘An eye for an eye.’ ‘Give them a dose of their own medicine.’ As children we have all suffered punishments for faults we have not committed, but the wound has soon healed. With Raven and Pinkie the wound never heals.

Raven as a Pinkie who has aged but not grown up is an interesting idea – Raven seems to be in his late twenties, while Pinkie, remarkably, is only 17. There is another link with Pinkie, too, in that Raven confesses to Anne that he cut the throat of a rival racecourse gang member, Kite – a murder which of course provides a mainspring for the plot of Brighton Rock, since Pinkie is a protégé of Kite. As for Raven believing that his crimes have an excuse, as Greene writes, there is of course his brutalised childhood and background, and Raven certainly comes to believe that ‘Others have committed worse crimes and flourish’ – specifically Sir Marcus, the man behind Raven’s assassination mission to central Europe. So Raven becomes not so much a fallen angel as a vengeful one, and while we don’t exactly approve of his activities, we have perhaps sympathy for his vengeance, and certainly none for Sir Marcus. From the very first pages of A Gun for Sale, Raven is an interesting and memorably chilling character, and one, by the way, well-depicted by Alan Ladd in the 1942 Hollywood film version of the book.

The man Raven tracks down and finally kills, Sir Marcus, is the most controversial of all in the novel. He is next in the line of Greene’s big businessmen, after Carlton Myatt in Stamboul Train and Erik Krogh in England Made Me. A very old, frail man, Sir Marcus is one of the wealthiest men in Europe. He has mysterious origins: Greene tells us, ‘He spoke with the faintest foreign accent and it was difficult to determine whether he was Jewish or of an ancient English family. He gave the impression that very many cities had rubbed him smooth.’ We are elsewhere told that ‘Sir Marcus had many friends, in many countries’, including it seems those in positions of power – friends who like him would do very well from the slide to war and the increased demand for metals and armaments. All this, and the added detail that Sir Marcus was a Freemason, has led Cedric Watts to conclude that ‘It seems depressingly obvious that Greene is offering the old anti-Semitic myth of a world-conspiracy of wealthy Jews to profit by war and death.’ It was a conspiracy theory current in the 1930s, and had been applied also to the war of 1914. Greene seems to goes out of his way to avoid saying that Sir Marcus was a Jew – his origins are shrouded in mystery, obfuscation, contradiction, but Greene does not help his case with the phrase ‘his nose was no evidence either way’. Certainly in later editions of the novel, Greene made no alterations to his depiction of Sir Marcus, and one is left with at the very least an uncomfortable feeling on the matter. I will return to Sir Marcus anon.

Part 2: ‘Men were fighting beasts, they needed war …’ (A thought of Anne Crowder, A Gun for Sale)

Let’s move on now to my second type of context, that of the historical background to A Gun for Sale. The book was written in 1935 and published in 1936, and the immediate historical context is the growing threat of war in Europe. In particular, there was a growing feeling that if Europe did get plunged into war, civilians would be under threat from air attack. In the First World War, British civilians had been bombed from the air by German Zeppelins and Gothas. In 1924 the Committee of Imperial Defence set up a subcommittee called Air Raid Precautions to see how the civilian population could be protected from aerial attack, and over the next ten years the needs were identified for gas masks, air raid shelters, evacuation of children and the blackout. Nor was this merely a bureaucratic concern: the threat of the bomber was part of ordinary people’s consciousness by the mid-1930s. As early as 1932 Stanley Baldwin had famously remarked on the uselessness of air defences in protecting civilians: ‘the bomber will always get through’. The Italian use of poison gas during the invasion of Abyssinia in 1935-6 reminded people of the dangers. In 1936, the year that Greene’s novel was published, the popular and influential film Things to Come, based on the book by H.G. Wells, presciently showed a great world war breaking out in 1940, and characterised that war as the indiscriminate slaughter of civilians in an air raid. Greene’s own review of Things to Come in 1936 comments on the ‘horribly convincing detail’ of the raid – ‘the lorry with loudspeakers in Piccadilly Circus urging the crowd to go quietly home and close all windows and block all apertures against gas, the emergency distribution of a few inadequate masks, the cohort of black planes driving over the white southern cliffs, the crowd milling in subways, the dreadful death cries from the London bus, the faceless man in evening dress dead in the taxi.’ These appalling scenes in a widely-seen film told British filmgoers what to expect if war came, and the events of the Spanish Civil War soon confirmed their worst nightmares: the air attack on the Basque town of Guernica in 1937 saw to that.

In A Gun for Sale, Greene has a long scene in Nottwich in which there is an air-raid drill in which civilians are required to put on their gas masks – which in turn gives an opportunity to Raven to hide his hair-lip as he seeks out Sir Marcus. Writing this scene in 1935, Greene himself was being remarkably foresighted. Despite the fear of air attack on civilians, air raid drills were scarcely heard of in 1935, and it was only in that year that a Home Office Committee was set up to coordinate the response to possible gas attack by air; and that same year saw the first government circular inviting local authorities to plan to protect people in times of war. But the Air Raid Wardens Service was not to be created until 1937, and local councils were not compelled to create ARP services until 1938. The readers of A Gun for Sale would thus have found Greene’s extensive depiction of a gas air raid drill novel, frightening, and, as time went on, remarkably prescient. Yet there is an irony here. Civilians were indeed targeted by bombs in the Second World War, in Britain, in Germany and elsewhere, but these were bombs that caused destruction and fire, not gassing. For reasons never wholly explained, gas attacks on civilians were not a feature of the new warfare of the Second World War. Greene’s emphasis on preparing for gas attack on civilians may have accurately foretold things to come, but such attacks never actually happened. Forty million gas masks in Britain proved unnecessary.

In A Gun for Sale, Greene has a long scene in Nottwich in which there is an air-raid drill in which civilians are required to put on their gas masks – which in turn gives an opportunity to Raven to hide his hair-lip as he seeks out Sir Marcus. Writing this scene in 1935, Greene himself was being remarkably foresighted. Despite the fear of air attack on civilians, air raid drills were scarcely heard of in 1935, and it was only in that year that a Home Office Committee was set up to coordinate the response to possible gas attack by air; and that same year saw the first government circular inviting local authorities to plan to protect people in times of war. But the Air Raid Wardens Service was not to be created until 1937, and local councils were not compelled to create ARP services until 1938. The readers of A Gun for Sale would thus have found Greene’s extensive depiction of a gas air raid drill novel, frightening, and, as time went on, remarkably prescient. Yet there is an irony here. Civilians were indeed targeted by bombs in the Second World War, in Britain, in Germany and elsewhere, but these were bombs that caused destruction and fire, not gassing. For reasons never wholly explained, gas attacks on civilians were not a feature of the new warfare of the Second World War. Greene’s emphasis on preparing for gas attack on civilians may have accurately foretold things to come, but such attacks never actually happened. Forty million gas masks in Britain proved unnecessary.

In the historical context of 1935-6, A Gun for Sale may also be seen as prescient in foreseeing a war on the horizon. War is averted in the novel, but there is a feeling at its end that the political tensions in the air will not go away, and that peace may be no longer-lasting than the upcoming marriage of Anne Crowder and James Mather. ‘This darkening land’, Greene writes, ‘was safe for a few more years’ – not a very comforting assurance. Certainly, in the world outside Greene’s novel, there were plenty of suggestions in 1935-6 that peace was under threat. Japan had invaded Manchuria in 1931, and Italy invaded Abyssinia in 1935. Hitler re-militarised the Rhineland in March 1936, breaking the terms of the Versailles Treaty, and the Spanish Civil War began a few months later. Noises of war were all around. Yet here again there is something of a paradox, for the war crisis in Greene’s A Gun for Sale does not look forward to the Second World War, but back to the First. There’s an assassination of a Minister of War in some Central European country, followed by an ultimatum which is accompanied by mobilisation and increasing war fever as the clock ticks down. This is 1914 being replayed – Princip’s assassination of the Archduke, Austria’s ultimatum, the countdown to war into which many countries will be drawn. In fact, Greene’s novel repeatedly goes out of its way to emphasise the parallels with the crisis of 1914, and its aftermath. Speaking of war, Anne says, ‘The last one started with a murder’. ‘It always seem to be the Balkans’, another character says. There are repeated references to No Man’s Land, and one to ‘the front trench’. The Mayor of Nottwich wears his Mons Medal and his Military Medal, and we are told that he had been wounded three times in the last war; the Chief Constable seems to relish the prospect of a new war in which he can resume his First War role of presiding over the local military tribunal and giving the ‘conchies’ a hard time; Sir Marcus reminiscences about the armaments needed for Haig’s assaults on the Hindenburg Line and reflects how in the war crisis Midland Steel is now more valuable than ever since November 1918, the end of the last war. And in the extract I read earlier describing early-morning Nottwich, there are references to Armistice Day, Haig poppies and the local War Memorial. If there is to be a second war, Greene seems to be saying, it will be one in the shadow of the first one, and even one not unwelcome to all. Graham Greene of course belonged to that generation which was too young to have fought in the First World War, but old enough to have heard the long lists of former pupils of his school who had lost their lives in the war. So his war crisis has none of Hitler and Mussolini, but much of Franz Ferdinand and Field Marshal Haig.

Then in A Gun for Sale there is the specific motive behind the war crisis. There are vaguely-drawn political tensions in Europe, but these are brought to the point of war by a political assassination, deliberately engineered to boost the profits of the makers of steel and armaments. Sir Marcus’s company is in a bad way: ‘It’s Midland Steel made this town’ a character says; ‘… But they’re ruining the town now. They did employ fifty thousand. Now they don’t have ten thousand.’ So Sir Marcus concocts his plan to have a politician shot and provoke a war. ‘Probably within five days’, Sir Marcus muses, ‘at least four countries would be at war and the consumption of munitions have risen to several million pounds a day.’ If this plot device of Greene’s seems far-fetched, some historical context may be of help. The treaty-makers at Versailles in 1919 saw the arms race among European powers as a background cause of the First World War, and the restrictions on German military might were intended to be part of a much more widespread process of disarmament, in which all countries would take part. More specifically, there was a left-wing critique which by the 1930s saw the last war, and possible future war, as the product of capitalism itself, in its drive for profits. Some authors identified and criticised the close links and vested interests shared by European governments and big arms companies like Vickers in Britain, Krupp in Germany, Skoda in Austria-Hungary/Czechoslavakia and Schneider-Creusot in France. In the years before Greene published his novel, a whole series of books was written exploring these links – these included Death and Profits (1932), The Bloody Traffic (1933), Salesmen of Death (1933), Iron, Blood and Profits (1934), and Merchants of Death: A Study of the International Armaments Industry (1934) by the American authors H.C. Engelbrecht and F.C. Hanigan. At the same time, a so-called ‘Peace Ballot’ organised in Britain during 1934-5 and focusing on issues of the League of Nations and Collective Security asked as one of its questions, ‘Should the manufacture and sales of armaments for private profit be prohibited by international agreement?’ Over 11 million people responded to the question, and over 90% said yes. With these books and that vote as a background, a Royal Commission enquiry was set up in Britain in 1935 to look at the issue of making and selling arms for private profit.

The Royal Commission on the Private Manufacture of and Trading in Arms met in Middlesex Guildhall, the building in Parliament Square which now houses the UK Supreme Court. In 1935-36 it had 22 sessions of evidence gathering and cross-examination, with contributions from a range of organisations and individuals. Lord Robert Cecil, who had attended the Disarmament Conference at Geneva in 1927, testified that

The Royal Commission on the Private Manufacture of and Trading in Arms met in Middlesex Guildhall, the building in Parliament Square which now houses the UK Supreme Court. In 1935-36 it had 22 sessions of evidence gathering and cross-examination, with contributions from a range of organisations and individuals. Lord Robert Cecil, who had attended the Disarmament Conference at Geneva in 1927, testified that

The influence of armaments firms tends to dampen the actual effort for peace. There had been cases in which active steps had been taken by great armaments interests to prevent the conclusion of disarmament negotiations. The most startling case was that of Mr Shearer who was employed by certain great firms in America to prevent the conclusion of the disarmament conference in Geneva in 1927.

In further testimony, Lord Cecil referred to the Chaco Wars between Bolivia and Paraguay, during which British armaments manufacturers had been supplying both sides and, effectively, fomenting the war. Former prime minister David Lloyd George asserted that rearming doubles the holding value of a company, whereas disarmament halves it. He argued that profiting from the sale of arms was immoral, and called for a state monopoly of arms production and sales. When the Royal Commission published its report in October 1936, it recommended unanimously that there should be more state control over the armaments industry. The report was quietly shelved, and little done.

This is the background to Graham Greene’s tale of Sir Marcus and war fever. And Greene himself had a direct interest in these goings-on. One of the witnesses before the commission was Fenner Brockway, whose book The Bloody Traffic had been critical of the armaments manufacturers Vickers in particular. Brockway was giving evidence on behalf of his left-wing political party, the Independent Labour Party. Greene himself was a member of the ILP for a few years in the mid-1930s, and he attended some of the sessions of the Royal Commission on armaments in the Middlesex Guildhall. In Ways of Escape, Greene writes that he cannot remember whether he attended because he was writing A Gun for Sale, or whether it was his attendance that gave him the idea. Either way, his attendance testifies to his interest in the issues surrounding the armaments industry. In Ways of Escape, he rather pooh-poohs the lacklustre nature of the Commission’s proceedings, writing:

My chief memory of the hearings is of the politeness and feebleness of the cross-examination. Some great firms were concerned and over and over again counsel found that essential papers were missing or had not been brought to court. A search of course would be made … there was a relaxed air of mañana.

Though he was critical of the proceedings, Greene realised from the hearings that here was a useful background to his planned thriller. His readers may not be as well versed in these issues as Greene himself, but the books on the armaments industry, the Peace Ballot and the Royal Commission would give his plot a plausible topicality.

And did Greene have any real-life equivalent in mind for his evil industrialist Sir Marcus? One of the likeliest candidates seems to be the notorious arms dealer, Sir Basil Zaharoff. Born in Greece in 1849, Zaharoff died peacefully in his bed, protected by bodyguards, in 1936, the year A Gun for Sale was published. Zaharoff was one of the richest men in the world during his lifetime, and was described as a ‘merchant of death’ and ‘mystery man of Europe’. His success was forged through his cunning, often aggressive and sharp business tactics. These included the sale of arms to opposing sides in conflicts, sometimes delivering fake or faulty machinery, and reportedly sabotaging trade demonstrations. He sold munitions to many nations, including Britain, Germany, Russia, Turkey, Greece, Spain, Japan and the USA. Zaharoff worked for Vickers, the British munitions firm, from 1897 to 1927, including one of its boom periods during the First World War. And he cultivated political friends – by 1915 he had close ties with David Lloyd George of the UK and Aristide Briand of France. Graham Greene is known to have read a biography of Zaharoff, and he was willing to declare in Ways of Escape that ‘Sir Marcus in A Gun for Sale is not, of course, Sir Basil, but the family resemblance is plain.’

__________

So what are we to make of this historical context of Greene’s 1936 novel? My suggestion is that we should see A Gun for Sale as more than just a thriller, but as having real political bite to it. In particular, I’d draw attention to two features of Greene’s plot. The first revolves around Sir Marcus. He is an emotionally empty, misanthropic ‘baddie’, but Greene is at pains to emphasise that he is part of a wider network of power. He is able to try to blackmail or bribe the chief constable into ensuring the police shoot to kill Raven, for instance. And his network is international: as war fever grows and Midland Steel’s share price rockets, Greene tells us this:

Sir Marcus had many friends, in many countries; he wintered with them regularly at Cannes or in Soppelsa’s yacht off Rhodes; he was the intimate friend of Mrs Cranbeim. It was impossible now to export arms, but it was still possible to export nickel and most of the other metals which were necessary to the arming of nations. Even when war was declared, Mrs Cranbeim had been able to say quite definitely, that evening when the yacht pitched a little and Rosen was so distressingly sick over Mrs Ziffo’s black satin, the British Government would not forbid the export of nickel to Switzerland or other neutral countries so long as the British requirements were first met. The future was very rosy indeed, for you could trust Mrs Cranbeim’s word. She spoke directly from the horse’s mouth, if you could so describe the elder statesman whose confidence she shared.

Here we have Sir Marcus not as an isolated misanthrope, but as part of an international nexus of powerful people with friends in high places. As we have seen,  Cedric Watts is distressed by what he sees as the tired anti-Semitism of this passage. But put that concern to one side for a moment, and what we have depicted here is international capitalism, red in tooth and claw and utterly amoral, unable or unwilling to see the dead bodies behind the glowing figures of the company balance sheet. A Gun for Sale at heart has a remarkably left-wing view of the world.

Cedric Watts is distressed by what he sees as the tired anti-Semitism of this passage. But put that concern to one side for a moment, and what we have depicted here is international capitalism, red in tooth and claw and utterly amoral, unable or unwilling to see the dead bodies behind the glowing figures of the company balance sheet. A Gun for Sale at heart has a remarkably left-wing view of the world.

The second feature of Greene’s plot that feeds into this world view concerns Raven himself. He is a hired killer, no more, no less, and we are told at the very beginning of the book that ‘Murder didn’t mean much to Raven.’ He was good at his job, he was being paid, so he didn’t need to ask who he was killing, or why. But in the long confessional scene with Anne in the railway shed, Raven begins to change his mind. Anne tells him about the politician he had killed:

Old what’s-his name. Didn’t you read about him in the papers? How he cut down all the army expenses to help clear the slums? There were photographs of him opening new flats, talking to the children. He wasn’t one of the rich. He wouldn’t have gone to war. That’s why they shot him. You bet there are fellows making money now out of him being dead. And he’d done it all himself too, the obituaries said. His father was a thief and his mother committed –

‘Suicide?’ Raven whispered.

So the scales fall from Raven’s eyes. Here was a man from a similar poor background to himself, a self-made man who has become a socialist politician and done good in the world. And Raven had killed him, at the behest of profiteering capitalists. Raven is apolitical no more, he becomes aware of social and political realities, becomes more than just a hired killer. As Raven later prepares to take his revenge and kill Sir Marcus, he tells him, ‘I wouldn’t have done it … if I’d known the old man was like he was.’ By the end of the novel, Raven has become a left-wing avenger, killing the international capitalist who had set him up.

Of course, we shouldn’t push this analysis too far. A Gun for Sale is, as Greene says, an Entertainment first and foremost, a thriller or shocker, melodramatic and designed to sell film rights to an American studio; hence, no doubt, British policemen firing guns on British streets. But just as Greene later dropped the division of his works into Entertainments and Novels, seeing it as having no fundamental validity, so we should not be blinded by the thriller form into ignoring what else A Gun for Sale offers. In Ways of Escape, Graham Greene wrote of the period 1933-37 as ‘the middle years for my generation, clouded by the Depression in England … and by the rise of Hitler. It was impossible in those days not to be committed…’ Impossible not to be committed: Greene’s own words. Critics have seen It’s a Battlefield, published in 1934, as Greene’s first political novel, part of this commitment. But we should see A Gun for Sale in the same way, the product of a writer who had joined the Independent Labour Party and attended meetings on the trade in armaments. A Gun for Sale is a thriller, but it’s a left-wing political novel too, a critique of international capitalism and what it does to the disadvantaged. At least, in the end, murder did mean much to Raven.

Mike Hill