This post also features an avid Graham Greene collector. Zoeb Matin [pictured] is a true Graham Greene aficionado. He lives and works in Mumbai which he prefers to call by its old name of Bombay. He shares an  important trait with GG himself – he is an inveterate bibliophile. Famously Greene used to haunt secondhand bookstalls and markets, sometimes with his brother Hugh, as a form of recreation. He even confessed that if he hadn’t been a novelist he would have liked to have been a secondhand bookseller. It is perhaps fortunate that he succeeded in his primary career choice.

important trait with GG himself – he is an inveterate bibliophile. Famously Greene used to haunt secondhand bookstalls and markets, sometimes with his brother Hugh, as a form of recreation. He even confessed that if he hadn’t been a novelist he would have liked to have been a secondhand bookseller. It is perhaps fortunate that he succeeded in his primary career choice.

Sadly, Zoeb’s article strikes a valedictory note. India is changing extremely fast. Thus he describes this article as ‘an ode to the secondhand bookshops of Bombay’ adding ‘they are all disappearing at an alarming rate’. As you will find, Zoeb captures this transient moment in his home city most evocatively.

In Pursuit Of Mr. Greene – Discovering Second-Hand Books in Bombay

One Bombay afternoon, I walked out of the air-conditioned comfort of Kitab Khana, one of the city’s most renowned and venerable old bookshops, into the stifling humidity and walked in a circle round the rusting but still regal Flora Fountain in the direction of the nearest station to catch a train home. I was disappointed, my stride was desultory; my hunt for a particular book by my favourite author had been thwarted by the absence of any of his paperbacks in the shelves of that bookshop. But then, I caught a glimpse of something that seemed to glitter in the haze of the sunlight. Behind the Fountain, on a pavement, beyond the zebra crossing, lay piles of books and behind them only more piles, forming a trench laden with treasures. And suddenly, a faint sense of hope returned to my heart. I walked across and was immediately accosted by those ever-helpful pavement salesmen, for whom I have a greater respect than the ones who are at a loss as to finding out books in an air-conditioned bookshop.

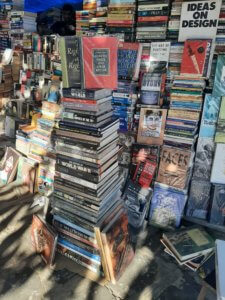

The books lay there baking under the sun and also basking under the shade of the drooping trees and suddenly, the noise of the traffic receded and seemed only like a minor nuisance that could hardly disturb or upset my little treasure hunt. And as I walked near one of the piles, I looked down at something that looked familiar, a name and a title that had been noted down in my memory for some purpose. GRAHAM GREENE was the name and A GUN FOR SALE was the title and at that moment, this humble pavement had been transformed into a subterranean, silent labyrinth that housed a precious jewel, the most priceless of them all. (Left: a typical Bombay bookstall)My purpose had been fulfilled, my journey to this old and still dignified part of the city had been justified. My disappointment was a distant, easily forgettable memory. And as I picked up that yellowing old Penguin edition, its cover blank except for that name and title printed in black, I knew that I was witnessing a miracle in broad daylight.

The books lay there baking under the sun and also basking under the shade of the drooping trees and suddenly, the noise of the traffic receded and seemed only like a minor nuisance that could hardly disturb or upset my little treasure hunt. And as I walked near one of the piles, I looked down at something that looked familiar, a name and a title that had been noted down in my memory for some purpose. GRAHAM GREENE was the name and A GUN FOR SALE was the title and at that moment, this humble pavement had been transformed into a subterranean, silent labyrinth that housed a precious jewel, the most priceless of them all. (Left: a typical Bombay bookstall)My purpose had been fulfilled, my journey to this old and still dignified part of the city had been justified. My disappointment was a distant, easily forgettable memory. And as I picked up that yellowing old Penguin edition, its cover blank except for that name and title printed in black, I knew that I was witnessing a miracle in broad daylight.

It was Greene who once equated hunting and scrabbling for rare discoveries and unexpected finds in second-hand bookshops as a “treasure hunt”. Why had I, then, been so blissfully ignorant hitherto till this afternoon of the many treasures that lay buried in these trenches, so many trenches too across the whole breadth of the city. Had I been conditioned for too long by the cold comfort of the popular bookshops with their bright lights and stench of instant coffee and noise of children gibbering like screeching birds over their storybooks? Had I then missed out on the thrill of this same treasure hunt all my youth and now that I was relatively older, and thrust with more responsibilities that would leave me with even littler time and opportunity? I was seized by this fascinating and fearful thought and I resolved then to make the most of the time I had before I grew too old and became a beast of burden to at least keep the treasure hunt going on and on.

That pavement behind the Flora Fountain was, of course, the most reliable in this respect. I visited it again a month later, famished for another taste of Greene and also thirsty for that relentless probing and prodding among the piles to find something new that I had not read yet. And, as promised, what emerged from that trove was The Comedians, not a classic Penguin edition, though. This particular edition was an American one and also a film tie-in. And so, instead of Paul Hogarth’s inky sketches of the fearsome Tontons Macoute, there was Richard Burton nuzzling Elizabeth Taylor, who sat frozen in an expression of agony and ecstasy, while those fine actors Alec Guinness and Peter Ustinov stared back in calm surprise and apprehension. But what’s in a cover? I bought it for a mere hundred rupees and treated myself to the luxury of a taxi; by the time I reached home, Brown had already returned to Port-Au Prince and Jones was nowhere in sight.

I returned to the pavement as and when I got the time and the opportunity and on a few more occasions, it helped me pick up even more of Greene than I could anticipate or expect. The Man Within was bought in December, the ideal time to be prowling around Bombay, which usually smoulders during the summer months and also becomes damp and wet during the rains. I remember my father browsing through the piles, hunting, in vain, for some rare book on the lifestyle and culture of the Nawab of Awadh and I remember my own skepticism about whether I would actually enjoy The Man Within, a novel not much talked about or praised in most circles, as much as I had enjoyed Brighton Rock my previous read. And I had already begun to read it as I walked through those empty streets and by-lanes of the old city on a Sunday afternoon and the first few pages of Andrew running helter-skelter for cover in the darkness of the evening gripped me like few opening pages of other novels do.

A year later, I bought A Burnt-Out Case – the tsetse fly perched on a withered skull was more persuasive than any other cover could have done. One associates Greene immediately with darkness and morbidity, moral and spiritual decadence and a perverse fascination for the world’s down-trodden, impoverished post-colonial bastions and yet, one is always surprised at the mesmeric, tender, compassionate ways in which he portrays this decadence and dystopia, without ever forgetting his first and foremost objective – of entertaining his readers with dense, multi-layered narratives rich with drama, romance and intrigue. Another year later, I bought May We Borrow Your Husband from the same place – this took some serious digging because it lay beneath all the other Penguin editions of novels I already had. A coagulated smear of dirty yellow had been formed on the cover and pages but that was what made this particular edition an even rarer treasure. Fresh-smelling, gleaming white pages of brand new editions now seemed like a sign of sanitised sterility; these yellowing, almost tattered and threadbare pages had all the marks of vitality, of urgency, of wear and tear and excitement.

For the other Greene books that I have tried to buy second-hand, there is one more interesting story that I recall most fondly. There is an old library stocked with old and second-hand editions and even, surprisingly, DVDs of old films, already an antique here in India, now that everybody watches films on their portable devices. It is called Victoria Book Library and it lies almost neglected in the corner of a desolate street leading one to the antiquated suburb of Dadar with its old tenements and weather-beaten bungalows of the yesteryears. The salty breeze from the Arabian Sea flows through this street, lending this shop, lit only by meagre neon tube-lights, the unmistakable air of a relic of another generation.

Inside, one afternoon, as I left my office earlier than prescribed, on a whim, I discovered a mild-mannered man neatly dressed in a starched white shirt and grey trousers and with eyes that stared in some bewilderment through his steel-rimmed glasses. He was courteous enough but it was a Friday, a day for his prayers and he needed to make a dash for the nearest place of worship and shut his shop for a few hours and he was already late. And yet, I prodded through the books, placed and crammed together on dusty shelves of rusted iron and among the many names that I found, Conrad, Maugham, Hardy, Dickens, Austen, I finally found Greene and picked it out. The book turned out to be an old, tattered edition of The Human Factor and I was so willing to buy it nevertheless, regardless of how it looked, that even he forgot his hurry and even threw in Doctor Frigo by Eric Ambler for free.

I have also discovered second-hand bookshops in the oddest corners and places in Bombay, where nobody would usually dream of looking twice. This happened most notably in Bandra, that suburb that is usually thronged by tourists keen on posing for photographs in front of the looming, lavish houses of film stars or shoot the sea breeze on the promenade; many young men and women even loll around the flea markets selling clothes, shoes, bags, goggles and trinkets on Hill Road or the Linking Road. Where can then one find something as congenial as a second-hand bookshop in a place so boisterous and bustling? As it happened, I discovered one, by sheer accident and curiosity, in the corner of a small, ramshackle shop that repaired bicycle and motorcycle tyres; it was small, dark and as fascinating as any cave with hidden treasures could be. But sorry, there was no Greene to be found, the shopkeeper consoled me, almost with patient regret. Unexpectedly, there was a thick, leather-bound edition of Sir Winston Churchill’s greatest speeches, with not even a single crease or stain on it. The shopkeeper informed me, rather proudly, that a man who had kept this and other rare old books had sold them to him before leaving Bandra for some other suburb up north. This particular edition was priced at nothing less than two thousand rupees. I wished if I could have enough space in my own inadequate book cupboard to accommodate this treasure of a different kind. I ended up buying an old PAN edition of Ian Fleming’s Goldfinger instead.

This was at least a case of a second-hand book seller who knew his wares. I had the misfortune to be once in a promisingly well-stocked second-hand bookshop whose proprietors were not even properly aware of what they were selling. This was in Powai, one of the newer, swankier residential suburbs near where I live and again, like Bandra, hardly a place to buy books. It was inside an old, now almost derelict shopping centre, darkened and dilapidated but there were still a few shops trying to ply a trade. This particular bookshop, air-conditioned as it was, could easily boast of a better collection than most of the well-known shops to be found in Bombay’s malls. But when I asked them to help me with finding some more of Greene, apart from The Quiet American and Brighton Rock, they were befuddled as to where they should search and looked around in bewilderment as if they were aware for the first time that the shop contained books. One of the assistants helped me to a pile of PG Wodehouse instead and as if encouraged by that simple initiative, I did end up buying Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves as a compensation for a day wasted. But at the counter, I could not help asking, “Can you find out if you have any Graham Greene in your stock and keep it for me when I come next? I live nearby only.” The shopkeeper, every bit a merchant, from his crinkly bush shirt to neat white trousers, merely replied, “I don’t know, sir, what are all these books. I don’t know where they are kept. It is not even mine, this shop. The family that runs it also does not know anything. They simply want to make money, you know.” [Right: The arch-monument Gateway of India: Bombay’s symbol of old Imperialism which foreign visitors flock to]

Many times, books bought from second-hand bookshops contain unexpected quirks that are as much relics of a bygone past as these editions themselves. On the inside flap of A Burnt-Out Case, I found a dog-eared library card, issued by the authorities of one of the city’s older colleges and the dates written in a column indicated all the times when it had been borrowed by any of the students. The years mentioned were between 1991 and 1993 and the name of the last borrower had been a Mr. Narvekar; I wondered who was this fine gentleman, more than 25 years older than me, belonging to a different generation altogether. Perhaps this generation had been of people who liked and enjoyed reading Greene. I had not known anybody else in my own college years or even among my present friends to read many books, let alone Greene or any other writer of the past. Most bibliophiles these days heed the advice of only bestseller lists in choosing what they would like to read.

There was one man, however, whom I encountered in a book sale, one sultry afternoon. I had been mulling over a second-hand edition of The Tenth Man for some time when this person, a man in his fifties, wearing a grey T-shirt and shorts over his gangling legs, noticed my predicament and reluctance. He walked over to where I stood and advised, with the wisdom of his age, “The Tenth Man is good, very good. Don’t miss it. It is not like his serious novels and more of an entertainment but it is very, very good at that. Take my word for it.” And that was all I needed to go ahead with my decision.

Library cards, stamps, signatures and certificates of scholastic proficiency are frequent but what was even odder and more wondrous was what I found inside The Comedians. It was an old BEST bus ticket, large and square and with the black ink faded into brown and I have often speculated as to its date – did it, like the library card, belong to 1990s, or was it even, and more fascinatingly, older than that? Could it be in the 1970s or 1960s? How would have BEST buses [left], those red, bulking behemoths that I still love so unreasonably, an indelible memory of my boyhood trips to college, looked back then? How would have Bombay looked back then, for that matter? So much had changed in this city even ever since I had been born but BEST Buses, like that pavement and these and many other second-hand bookshops, had probably remained as they were. All I had to do was to go and discover them again.

Library cards, stamps, signatures and certificates of scholastic proficiency are frequent but what was even odder and more wondrous was what I found inside The Comedians. It was an old BEST bus ticket, large and square and with the black ink faded into brown and I have often speculated as to its date – did it, like the library card, belong to 1990s, or was it even, and more fascinatingly, older than that? Could it be in the 1970s or 1960s? How would have BEST buses [left], those red, bulking behemoths that I still love so unreasonably, an indelible memory of my boyhood trips to college, looked back then? How would have Bombay looked back then, for that matter? So much had changed in this city even ever since I had been born but BEST Buses, like that pavement and these and many other second-hand bookshops, had probably remained as they were. All I had to do was to go and discover them again.

Zoeb Matin