Our Quarterly Magazine

A Sort of Newsletter: A Quarterly Magazine

The Trust publishes a quarterly magazine, each February, May, August and November, titled A Sort of Newsletter (ASON). Friends of the Trust receive free print copies as part of their membership. Each issue contains a rich mix of articles, reviews, correspondence and news. ASON is not intended to be an academic journal; there is something for everyone with an interest in the writer.

The Trust publishes a quarterly magazine, each February, May, August and November, titled A Sort of Newsletter (ASON). Friends of the Trust receive free print copies as part of their membership. Each issue contains a rich mix of articles, reviews, correspondence and news. ASON is not intended to be an academic journal; there is something for everyone with an interest in the writer.

Rarely does a month go by without Graham Greene featuring in the news in some form or other. A Sort of Newsletter will keep you bang up to date with information about the latest Greene-related books, films, reviews and associated news from around the world.

The annual Graham Greene International Festival, held in September each year in Berkhamsted is the principal event in the Birthplace Trust’s calendar. Naturally, it features prominently in the pages of the newsletter with information about forthcoming festival appearing in the May and August issues followed by retrospectives on each event in the November issue.

So, if you are interested in Graham Greene, his life and his books and you are not currently a Friend of the Graham Greene Birthplace Trust, then you are urged to turn to the Members’ page on this website which gives all the details about joining and receiving A Sort of Newsletter.

____________

SOME TASTERS

To give you a flavour of what to expect to find within the pages of the magazine, we regularly publish features from the last four issues :

ISSUE 97 February 2024

ARTICLE

Stuart Maye-Banbury and Angela Maye-Banbury live on Achill Island, County Mayo in the Republic of Ireland. They are both great admirers of Graham Greene’s work. Stuart is a composer, writer and guest lecturer specialising in music and memory. Angela, a scholar of place, memory and meaning, is the Founder and Chairperson of Achill Oral Histories and Emeritus Fellow in Oral History at Sheffield Hallam University.

Ache of Heart: The impact of Achill Island on Graham Greene’s life and work

‘A story has no beginning or end: arbitrarily one chooses that moment of experience from which to look back or from which to look ahead.’ So Greene wrote in the opening line of The End of the Affair. As we entered the Dooagh cottage on Achill Island on the stormy evening of 10 August 2023, it too felt like a census point in the ever-evolving Greene/Walston Achill story. John O’ Donnell, who had returned to Achill from Cleveland with his family, had generously agreed to show us around the cottage which is located next to his family home. As Mr O’ Donnell shone his torch to guide us safely through the door, our own portals of the imagination began to open. We were entering the place where it all began – Greene’s exhilarating and intensive thirteen year-long affair with Catherine Walston, an experience which was to impact on his work most profoundly. Greene and Walston first stayed in the Dooagh cottage in April 1947 and were frequent visitors there until 1949. Yet despite the palpable impact of Achill on Greene’s work, we know little about Greene’s time in Dooagh. If these rustic Irish walls could talk, they most certainly would have a tale to tell.

The cottage, now boarded up, sits a fraction off the main road up the hill from Gielty’s Bar, reputedly the westernmost pub in Europe and just a stone’s throw away from the current home of John ‘Twin’ McNamara, the island’s most respected bard. It is modest in its design and languishes in plain sight. But its views are far from ordinary – it sits a stone’s throw from the mighty Atlantic Ocean with magnificent views of Achill, Clew Bay, Clare Island and beyond. At the height of the tourist season, thousands of visitors pass by the Dooagh cottage oblivious to the fact that in the late 1940s, it played host to one of the most respected authors of the 20th century. Achill Island, Ireland’s biggest island, is renowned for its sublime landscape, traditional way of life and the gentility of its people. For centuries, it has been a magnet for writers, artists and musicians. Greene was captivated.

Walston had chosen the situation of her Achill retreat astutely. It was the perfect retreat for Greene who yearned for tranquillity to write undistracted. ‘I so long for somewhere like Achill or Capri where there are no telephones’, he later wrote to Catherine in 1950. The simplicity of the lifestyle in Achill, as a temporary interlude, suited them both. The cottage sits on the farthest outskirts of the townland of Dooagh on the gradually inclining road that stretches from the industrious hub of Achill Sound to the isolated splendour of Keem Bay.

Greene, then aged 43, was in love. For Greene the writer, the word ‘Achill’ evoked a Proustian rush of memory. Walston’s Achill cottage became synonymous with love, liberty and languor. Today, Greene’s presence in Achill may well be conspicuous by its absence. But there is no shortage of evidence about the profound impact his time on the island had on his work. Achill unleashed Greene’s imagination enabling him to write what is arguably some of his best work. With Catherine Walston at his side, the tranquillity of Achill stood in sharp contrast to the torment of the act of writing. Greene’s novel The End of the Affair was inspired by his time with Walston in the Achill retreat. It was also in Achill where Greene worked on The Heart of the Matter, published in 1948 but ironically banned in Ireland. He also worked on the film versions of The Fallen Idol, Brighton Rock and The Third Man as well as writing some of his best poetry in Achill. His collection of love poems, After Two Years, published two years after his first stay in the Dooagh cottage, reveals his intense feelings for Walston. Only 25 copies were printed and distributed to Greene’s family and friends. In a poem in the collection, Greene wrote: ‘In a plane your hair was blown, and in an island the old car lingered from inn to inn like a fly on a map. A mattress was spread on a cottage floor and a door closed on a world, but another door opened.’ A further collection, After Christmas, was published in 1951, with only 12 copies printed. These intimate collections, comprising two tiny volumes, were the sole output of the Greene’s publishing house the Rosaio Press. Greene found his experiences on the west coast of Ireland intoxicating. On his time in Achill in the late 1940s, he wrote ‘I who learned Ireland first from you.’ After returning from his second stay in Dooagh in August 1947, he told Walston that ‘Ireland is breaking in on me irresistibly.’

Writing to Catherine Walston in 1949, Greene said: ‘Somehow I feel an awful reluctance and ache of heart when I address the envelope to Achill. That was where we began […] we probably would never have done more than begin if we hadn’t had these weeks, but only an odd couple of days in England […] I wish I could make you feel, not just by faith, how missed you are the moment the door closes and how life begins when the door opens.’ The door to which he referred was both literal and metaphorical, a portal into new opportunities of both heart and mind. It was the physical entrance to the cottage where he first stayed with Catherine Walston, née Catherine Macdonald Crompton. Walston, born in New York State, was the beautiful bohemian wife of wealthy landowner, Labour Party politician and later peer Henry Walston. Greene too was married to Vivien Dayrell-Browning, a talented poet in her youth who was working for Blackwells in Oxford at the time of their meeting. Greene and Walston’s affair had an air of inevitability with their respective partners watching helplessly as the affair gathered pace.

Yet despite the widespread critical acclaim Greene’s work received, his time on the island has been consigned to the margins of history and is fading faster with each passing day. Other than a cursory reference to Greene’s work on Achill Tourism’s ‘Arts and Culture’ web pages, the now privately-owned cottage is neglected entirely on the tourist trail. There is no plaque to signify the literary status of its former occupant. Nor is there any signage to indicate Greene’s presence on Achill. Perhaps most significantly, not one volume of Greene’s writing is to be found for sale on the island. On face value, the dearth of information on Greene’s time on Achill may seem a curious omission on an island that depends on tourist attractions for its summer months’ life’s blood. However, the reason for this is not hard to unravel. Greene’s peripatetic lifestyle stands in sharp contrast to Achill’s other noted author, Heinrich Böll who lived full-time on the island and is now represented by a writer’s retreat, festival and foundation. Consequently, memories of Greene’s visits to Achill are less enmeshed in the collective and cultural memory.

In 1999, Oliver Walston visited Achill some forty years after he was there as a child to reconnect with the cottage which had proved pivotal to his mother’s affair with Greene. Although the affair technically began outside Rules Restaurant in Maiden Lane London, Oliver Walston believes that it was Achill where Walston and Greene’s relationship truly flourished. Speaking in the BBC documentary ‘The Beginning of the End of the Affair’ (broadcast in 2000 to coincide with the opening of Neil Jordan’s film about Greene and Walston’s affair), Walston explained, ‘This was the first time she’d ever had a house of her own. It meant a terrific amount to her. This house is, I think, actually where the affair began … And 10 years later in April 1957, he wrote her a letter saying “Ten years ago, it all started in Achill.”’

The work of French philosopher Pierre Nora reminds us of the fallibility of memory and with it, the importance of marking these important lieux de mémoire (sites of memory) and the people with whom they are associated so we may remember never to forget. The relationship between people and place is intimate and complex. The Dooagh cottage is one such site of memory, an enduring feature on Achill’s landscape which played host to one of the most celebrated writers of the twentieth century.

Stuart and Angela Maye-Banbury

____________________

ISSUE 94 May 2023

ARTICLE

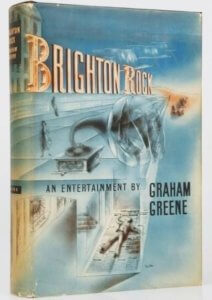

Brighton Rock: the US first edition

The extensive coverage in February’s ASON of two variant opening sentences of Brighton Rock (’Hale knew …’) came to the conclusion that the US and the British first editions had different starts: ‘Hale knew that they meant …’ for the US, ‘Hale knew, before he …’ for the British. One reader has since suggested that the US edition went straight to the point about murder, rather than leaving it to the end of the sentence, because that suited the American temperament. Perhaps so; maybe we Brits can wait a few moments for our thrills. One thing to add to that whole debate, though: the US edition was actually published in June 1938, before the British release in July. So you could argue that ‘Hale knew that they meant to murder him before he had been in Brighton three hours’ is the true original version, even though the sub-claused British version now reigns supreme.Leaving aside that whole question of the novel’s opening sentence, that first US edition of Brighton Rock continues to cast a shadow. Lucas Townsend emailed with some questions to ask about his US edition of the book, as follows:

‘… my first copy of Greene’s Brighton Rock I owned I purchased in 2019 in the USA, and it is the 2004 Penguin Centennial Edition (with the watercolor(?) art of presumably Pinkie on the cover. The other centennial editions in this style were Orient Express, The Heart of the Matter, The End of the Affair, The Quiet American, and Travels with My Aunt).

‘Now, on the very last page of the book – not page 269, which contains the closing lines about Rose walking towards “the worst horror of at all” – but rather, page 270, contains the following passages with no detailed explanation of who actually put them there:

‘ “NOTE TO AMERICAN READERS

‘ “During the summer season in England certain popular newspapers organize treasure hunts at the seaside. They publish the photograph of a reporter and print his itinerary at the particular town he is visiting. Anyone who, while carrying a copy of the paper, addresses him, usually under some fantastic name, in a set form of words, receives a money prize; he also distributes along his route cards which can be exchanged for smaller prizes. Next day in the paper the reporter describes the chase. Of course, the character of Hale is not drawn from that of any actual newspaperman. – G.G.

‘ “Brighton Rock is a form of sticky candy as characteristic of English seaside resorts as salt-water taffy is of the American. The word ‘Brighton’ appears on the ends of the stick at no matter what point it is broken off. – E.D. ”

‘Several questions here! Presumably “G.G”. is Greene, but when did he write this? Was this from the first Viking Press edition in America, or sometime later? Why is it in the back of the book, and not the front? Is this in every American edition? And who is “E.D.”? Surely an editor would say “Editor” or “ED.” with no period in between?

‘Presumably this information would be helpful for a first-time reader of the book, and should go on the front page; I certainly had no clue what Brighton Rock (the sweet) was when I first read it in the States and did not understand what Hale’s role was, until I saw this note on the last page…’

I can I hope answer all Lucas’s queries. First, ‘G.G’ is of course Graham Greene, and his note about the ‘treasure hunt’ organised by British newspapers was included in the ‘Note’ in the first US edition in 1938. Presumably US newspapers had not adopted the idea by the late 1930s. ASON readers may be interested if I expand on Greene’s words on the whole business by quoting from Wikipedia’s entry on ‘Lobby Lud’, the original for Greene’s ‘Kolley Kibber’:

I can I hope answer all Lucas’s queries. First, ‘G.G’ is of course Graham Greene, and his note about the ‘treasure hunt’ organised by British newspapers was included in the ‘Note’ in the first US edition in 1938. Presumably US newspapers had not adopted the idea by the late 1930s. ASON readers may be interested if I expand on Greene’s words on the whole business by quoting from Wikipedia’s entry on ‘Lobby Lud’, the original for Greene’s ‘Kolley Kibber’:

Lobby Lud is a fictional character created in August 1927 by the Westminster Gazette, a British newspaper, now defunct. The character was used in readers’ prize competitions during the summer period. Anonymous employees visited seaside resorts and afterwards wrote down a detailed description of the town they visited, without giving away its name. They also described a person they happened to see that day and declared him to be the ’Lobby Lud’ of that issue. Readers were given a pass phrase and had to try to guess both the location and the person described by the reporters. Anyone carrying the newspaper could challenge Lobby Lud with the phrase and receive five pounds (about £320 in 2023).

The competition was created because people on holiday were known to be less likely to buy a newspaper. Some towns and large factories had holiday fortnights (called ‘wakes weeks’ in the north of England); the town or works would all decamp at the same time. Circulation could drop considerably in the summer and proprietors hoped prizes would increase it.

The character’s name was derived from the paper’s telegraphic address, ‘Lobby, Ludgate’.

The British colloquial phrase ‘You are (name) and I claim my five pounds’ is associated with Lobby Lud, despite being based on a similar idea thought up by a different paper.

After the demise of the Gazette in 1928 the competition continued in The Daily News, which became the News Chronicle from 1930, in turn being absorbed into the Daily Mail in 1960. Other newspapers such as the Daily Mirror ran similar schemes. ‘You are (name) and I claim my five pounds’, the most well-known phrase, seems to date from a Daily Mail version after World War II. A train, the Lobby Lud Express, was run to take Londoners to resorts Lobby visited.

In 1983 an original Lobby Lud – William Chinn – was discovered aged 91 in Cardiff, Wales. The Daily Mirror‘s ‘Chalkie White’ continues to visit resorts, and the idea has been taken up by local radio stations and other media, often offering lesser prizes.

It’s perhaps worth adding that Greene’s name ‘Kolley Kibber’ – Fred Hale’s equivalent of Lobby Lud in Brighton Rock – is in turn based on Colley Cibber (1671-1767), an English actor-manager, playwright and, from 1730, Poet Laureate.

But back to Lucas’s queries. He is right of course that ‘E.D’ should be ‘ED’, standing for ‘Editor’ – LibDem leader Ed Davey has not started moonlighting by editing Graham Greene’s novels. The ‘ED’ note was also included in the 1938 Viking Press US first edition of the novel, along with Greene’s own note, and presumably each subsequent US edition of the novel. (In fact, I have a 1997 Folio Society edition of the book, published in the UK, which also contains the ‘Note to American Readers’.) As the accompanying illustration of the US first edition shows, that edition has simply ‘Note’ as the heading, not the ‘Note to American Readers’ that Lucas’s edition has – presumably it was assumed that the 1938 edition would only be read by American readers, so there was no need to specify that, while in the internet age the Centennial Edition would be read worldwide, not just in the USA.

However, I have not been able to establish the name of Greene’s American editor in 1938 – presumably the one who settled on ‘Hale knew they meant to murder him…’ as the opening sentence: can any ASON reader shed any light on the editor’s identity?

As an American reader of Brighton Rock, Lucas is not alone in needing the editor’s help in explaining the very British idea of ‘rock’ as a long, hard, round stick of candy popular at seaside resorts. No doubt the problem for non-Brits partly explains why the 1947 film version of Brighton Rock was given the title Young Scarface in the USA, and also why a French Livre de Poche edition of the novel in the 1960s had the title Les rochers de Brighton, with a cover illustration of a steep rock face.

Finally, I can only agree and sympathise with Lucas’s point about the ‘Note to American Readers’ being placed at the back of the US, Centennial edition he read. Not very helpful. But in the 1938 first Viking edition, the ‘Note’ is at the beginning, as it should be – immediately after the Dedication page.

Mike Hill

_____________

ISSUE 93 February 2023

ARTICLE

Hale knew

Hill knew, before his article had been released three hours, that they meant to respond to it.

A quick recap. In the November ASON [see Issue 92 extract below], I pointed out that the opening sentence of Brighton Rock is ‘Hale knew, before he had been in Brighton three hours, that they meant to murder him.’ Yet in the BBC Arena documentary, shown at last year’s Festival, this is rendered as ‘Hale knew that they meant to murder him before he had been in Brighton three hours.’ – and this rendering was made in the voice of Sir Alec Guinness, no less, with an image of the first paragraph of the novel, complete with this version of the opening. So I asked ASON readers a series of questions about this discrepancy – and they responded.

First, is there any difference of meaning between the two? Colin Garrett points out an ambiguity in the ‘BBC’ rendering: ‘In the Arena version it is not clear whether the three hours refers to the knowing or the murdering. In Greene’s version it is clear that Hale knew within three hours but did not know when the murder would be.’ Zoeb Matin agrees: ‘The modified sentence quoted by Guinness has a flaw in it – is the gang about to kill Hale before he has been in Brighton for three hours or is it the other way around – that Hale realised it, as he did, of his fate at that time? So, without a question, Greene’s original line is what still works today.’ So the ‘non-BBC’ version is to be preferred not least on the grounds of clarity – though in defence of the Arena programme, I have to point out that Guinness’s reading goes up at the end of the quoted sentence in a way that avoids this ambiguity – not something that happens if simply read in one’s own head, as it were.

My next question was, how did this discrepancy between the two versions come about? One possibility is that the Arena version comes from a different edition of the book. David Hawksworth emailed to say that in his collection of Greene books he has two copies of Brighton Rock which start with the Arena first sentence – a US Compass Book Edition from August 1958 (his copy is the tenth printing from November 1965, with a reference to the 1938 US Viking Press edition) and an Invincible Press ‘Rare Australian Pulp issue’, 1944. David sent photographs of the two front covers and first pages, and are shown here (with the Australian cover on the left).

This Australian edition is interesting, since the text omits big chunks of the plot, and seems to be a bastardised version of the novel, probably an unauthorised one, and affected by the wartime paper shortage. Crucially, the text follows the US Viking Press first edition of 1938, rather than the UK first edition of the same year – for instance, in having ‘Drewitt’ rather than ‘Prewitt’ as the name of the dodgy lawyer. Hence, both David’s copies are based on that original 1938 Viking Press, New York US first edition. Was that where the Arena-style first sentence originated? I don’t have a copy of that edition, so I emailed a few booksellers who were advertising such a copy for sale, and the answer came back – yes, that edition does indeed start with ‘Hale knew they meant to murder him before he had been in Brighton three hours.’ That edition is known to vary from the UK first edition in a few respects – not just Drewitt/Prewitt, but in omitting some of the Jewish references, too. And the US first edition was in turn the basis of early Penguin and Bantam paperbacks of the novel, as well as the two editions David Hawksworth owns. But the Collected Edition of Brighton Rock in 1970 followed the UK first edition of 1938 and used ‘Hale knew, before he had been in Brighton three hours, that they meant to murder him’ as its first sentence, and subsequent editions, including the later Penguin and Vintage Classics texts, follow that – including the US Penguin Centennial Edition of 2004. So the copy you are likely to have on your bookshelves, dear reader, has the ‘Hale knew, before…’ opening, not the US 1938 one – but it seems that Arena had a copy based on the latter, and used it in their documentary on Greene. Case solved.

But not so fast. ASON reader David Butler-Groome wrote with another intriguing possibility. David has read and recorded audiobooks semi-professionally for the last few years, and his suggestion is that ‘Alec Guinness probably made the decision to read that sentence in that way in the studio at the point of recording.’

He explains this thought in detail: ’He could deliver the line with less interpretation and less imposition of his own acting technique by putting the sub-clause at the end and keeping the main clause unbroken and therefore make the delivery less about the actor and more about the text. If you try to perform the two versions, the proper one does not scan aurally as easily as the rewritten version – if you have never read the book, which is an important consideration …

‘Whichever way it is written, grammatically the main clause of the sentence is “Hale knew […] that they meant to murder him”. The sub clause could come before or after, or as Greene has it, in the middle.

‘It seems to me that the sentence “Hale knew that they meant to murder him before he had been in Brighton three hours” is rendered without punctuation and aurally scans as one sentence with the meaning derived efficiently, with the main clause first and the sub-clause second.

‘The proper version “Hale knew, before he had been in Brighton three hours, that they meant to murder him” requires the visual punctuation to determine the clause within the middle of the sentence. The commas indicate a cognitive shift in the determination of meaning. With these two pieces of information in one sentence with a broken main clause, the reader has to do more work and this engages the reader actively in the creation of the narrative voice, which is what every writer wants: engaged readers.

‘This is not necessary when you have a voice actor interpreting the narrative voice for the reader. When listening to an audiobook the active “reader” becomes the passive “listener”. The listener has no access to the visual punctuation, they cannot scan the sentence in advance as it looms up on them from the page, they cannot gauge its length visually on the page, they are guided by the voice actor as to the interpretation. They need aural prompts and sometimes this means that listening is a less engaged experience than reading for oneself.

‘In order to deliver the Hale sentence as Greene intended, I would argue that the voice actor has to do a lot of aural signposting, to pause the main clause, introduce the sub-clause and then reintroduce the main clause, as they are written – which can be dispensed with by moving the sub clause after the main clause. I would argue that reading the sentence the way Alec Guinness did, more cleanly conveyed to the listener, with no loss of effect or change in the intended meaning by Greene.’

The only problem with that approach, as David admits, is if viewers of the Arena programme are so familiar with the opening sentence as to feel a mistake has been made: my problem entirely. David also suggests that, Guinness having made the decision to read the opening sentence as he does, it fell to the Arena documentary makers ‘to mock up the opening paragraph to avoid confusion.’

So we have two possible answers to my question about why Arena did what it did:

either they used a Viking Press-based copy of the novel, or Alec Guinness decided to read the sentence in that way. You choose.

My final question was, is the ‘UK’ version of the opening sentence to be preferred to the US/Arena version? Our readers are unanimous that it is, quite apart from the potential ambiguity of the US version, already discussed.

Neil Sinyard has this to say:

‘Greene’s version is much to be preferred to the Arena one. It seems to me that Greene has taken great care with the rhythm, suspense, and the delayed revelation of the sentence, all controlled by the punctuation, so that the full weight will fall on the last phrase and on the word “murder”. You completely lose that in the Arena version which seems to me clumsier in construction and less effective.

‘And incidentally: Greene would undoubtedly have known (he might even have been influenced by the thought) that his hero Joseph Conrad took four days over the composition of the last sentence of Heart of Darkness, weighing the words, controlling the tempo (which gets slower and slower) so that the full impact will fall squarely on the novella’s very last word: “darkness”.’

Lucas Townsend agrees:

‘Greene’s version is simply better. The use of commas enforces effective, narrative-driving pauses in the writing, something that the Guinness BBC version lacks; there is no suspense (even the minuscule amount of suspense a single opening line could offer) in the Guinness BBC version. Greene’s use of commas speaks to what Roland Barthes calls in S/Z the introduction of textual “enigmas.” In other words, books ask questions (“enigmas”), and Greene’s version, through the comma pauses, asks four, and answering the questions only asks more: “Hale knew [1. knew what?], before he had been in Brighton three hours [2. why is he in Brighton only three hours?], that they meant to murder him [Q1. answered. 3. who is they? 4. why are they meaning to murder him?]. The Guinness BBC version, comparatively, seemingly asks one question, and then seemingly answers it in the same sentence [1. Hale knew what? Q1 answered. That they meant to murder him.]; it lacks the suspense that carries us through the remainder of the opening chapter of Brighton Rock. I think we should be very glad that Greene is concerned with the effect of his sentence-structures, and that he wrote it the way he did.’

Zoeb Matin puts his preference this way:

‘I feel that the original line, used by Greene to open the novel, is perfect and ideally it should be quoted in its original form only. There are two simple but essential reasons why – the first, of course, is the technical reason. Greene always adhered to a writing style that, while crisp and succinct, would never compromise on grammar and linearity and thus, by default, the original line, especially in its clear delineation of place and time (“Brighton … three hours”) very clearly defines what is happening and where and when it is happening.

‘But the second reason is that of an equal clarity in storytelling and the significance of an event. The first sentence strikes the reader like a jolt, immediately plunging him or her in the place of Hale, in the throes of danger of certain death. But as the remaining words and sentences of the first chapter begin to trickle in, Greene introduces to us the world of Brighton on a weekend, teeming with holiday crowds and then reveals how Hale is trying to follow his specified path as per his itinerary, from one place to another. It is less than three hours, then, exactly as Hale encounters Pinkie Brown in the bar and the latter’s spare, sinister threats as well as his furious gesture of throwing a glass and thus leaving the bar without negotiating any further with Hale, leaves us and him in no doubt of the intentions to kill him. And thus, the opening line, like a prophecy of what is about to happen, fits in seamlessly. When one reads it aloud, especially the part of “before he had been in Brighton three hours”, one knows exactly what and when has happened and the significance of that incident to what follows in the hours after that.’

So there we have it. The UK first edition version is to be preferred, both on grounds of clarity and for punch and effectiveness, than the US first edition/Arena version. Interestingly, the original manuscript of Brighton Rock seems to have disappeared, so we can’t check what Greene originally wrote in that first sentence. But my strong feeling is that he wrote ‘Hale knew, before he had been in Brighton three hours, that they meant to murder him’, and that’s what was used in the original, UK first edition in 1938 – and thankfully has become the standard rendition now. I’ve always been slightly puzzled that the editor of the US first edition changed ‘Prewitt’ to ‘Drewitt’ (why ever would you do that?), but now we have a bigger mystery. Why did that editor change the opening sentence to something much less effective, and why did Greene agree to the change?

A very final thought on the Arena version. I notice that early on in Brighton Rock Graham Greene writes about Ida Arnold’s ‘smooth Guinness voice’. Perhaps that’s why Arena used Sir Alec.

Mike Hill

[Absolutely no excuses are offered for the selection of this month’s extract from A Sort of Newsletter on the same subject of Brighton Rock’s opening sentence. The quotation engendered serious and valuable analysis for both for Greene enthusiasts and scholars]

____________________________

ISSUE 92 November 2022

ARTICLE

Hale knew

Towards the end of the BBC Arena documentary shown at this year’s Festival, the story reaches the publication of Brighton Rock, Greene’s first great novel, published in 1938. The first page of the book appears on screen, and we hear Alec Guinness reading the opening paragraph, beginning with the famous opening sentence: ‘Hale knew that they meant to murder him before he had been in Brighton three hours.’

Eh?

Jean and I had arrived home from this year’s Greene Festival before I could think about the buzzing in my head from that reading. The first sentence of Brighton Rock isn’t that, is it? Surely it’s ‘Hale knew, before he had been in Brighton three hours, that they meant to murder him.’? I have, I find, five copies of the novel on our bookshelves (I know, I must stop buying stuff), and each of them has this latter opening, not the one quoted in the Arena programme. But perhaps different editions have differing versions of that sentence? I checked on the internet, and could find no version that matched the Arena one – except a chap on Twitter who praised the sentence as the best opening of any novel in the English language, then gave the wrong rendering. The simple truth is that for some reason Arena got it wrong. Perhaps one of the programme-makers simply relied on memory of the sentence, then arranged for Alec Guinness to read that version and had a mock-up of the first page done to show as the reading is heard. Or did they (or even Alec Guinness?) decide that the wrong version sounded better to read?

Am I wrong about what the right version is?? If any ASON reader knows better than I do, I’d like to hear.

More generally, it’s interesting to compare the two versions of that famous first sentence. Graham Greene was a master of clear English prose – the day before he died he famously added a comma to the so-called ‘deathbed letter’ to make clear his precise intention regarding quoting from copyright material. As anyone who has read his works or examined his manuscripts knows, Greene cared enormously about the length and balance and weight of his sentences, and he chose to open Brighton Rock with ‘Hale knew, before he’d been in Brighton three hours, that they meant to murder him.’ So here’s a challenge to ASON readers. Let me know what you think of the two versions of the sentence – what if anything is the difference in meaning between them, and why you think Greene chose the one he did – and whether there is any reader out there who prefers the Arena version. I’ll publish any thoughts in the next ASON.

Mike Hill

_________________

ISSUE 91 August 2022

OBITUARY

I.M. Francis Charles Bartley Greene (1936-2022)

Born just as his father Graham Greene was achieving fame and withdrawing into affairs with Dorothy Glover and others, Francis Greene saw little of him in childhood. He and his elder sister Caroline were raised by their mother Vivien.

Educated by the Benedictines at Ampleforth College, he went up in 1954 to Christ Church, Oxford, where he read physics and began to study the Russian language, as a prelude to a number of journeys behind the Iron Curtain. National Service brought him to the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment at Aldermaston just as his father was writing Our Man in Havana. He took a desk job at the Foreign Office but turned down a career in MI6, before moving to the BBC where he worked on the science programme Tomorrow’s World. As a freelance photo-journalist in 1967-8 he came close to being killed in both Israel and Vietnam.

In 1971, he married Anne Cucksey, whom he had met at the BBC, and the two eventually occupied a mediaeval house near Axminster, which Francis, a skilled carpenter, renovated with his own hands.

From the late 1980s, he became intensely involved once more in Russia, financing the publication of works gleaned from KGB archives, which have since been shut down again. As an anonymous donor, he paid for a Russian version of the Booker Prize. He was a great supporter of Memorial, the human rights organization founded by Andrei Sakharov, and of environmental organisations researching nuclear pollution in Russia. He despised Vladimir Putin and assured me almost twenty years ago that the world could expect trouble from him.

Towards the end of his father’s life, Francis took charge of his business affairs, and then, after Graham’s death, continued for three decades as a very active literary executor. Although a patron of the Graham Greene International Festival he did not attend its events as he could not bear being fussed over.

After a period of declining health, Francis died on 13 April 2022, and is survived by Anne Greene. Although I cannot claim to have known him very well, as he was a decidedly reserved man, yet I have to say that I treasured our friendship and will miss him always.

Richard Greene

________________